Visit to Takao Hayashi in Tokyo

By Hermann Zapf

During my short visit to TypeBank in 1988 Mr. Takao Hayashi asked me, while discussing Japanese letterforms, to try some Japanese characters with a brush. The same request was made several times on other occasions during my two visits to Japan in 1982 and 1988. But I always refused, for I had too much respect for written Japanese letterforms.

As a type designer you can imitate characters in any language – even Arabic and Hebrew – but I think you should never attempt to imitate Japanese calligraphy. The reason may be that it is the secret of this highly cultivated art in Japan to first study handwriting with a master. Sometimes it takes many years to get a satisfactory result in order to please the unmerciful and critical eyes of your writing master. To reach perfection is for many only a dream.

There are several reasons why it is so difficult to write with a brush in the Japanese manner. First, the position of the elbow and the proper grip to hold the brush is completely different from the method used in Western countries. We admire the absolute control seen in the calligraphy examples of your great masters. They have developed this over the course of centuries, and also defend it as a highly respected skill today. As you know, this training to acquire good letterforms demands a lot of concentration, as well as intensive study of the spirit of Japanese, the history of the letterforms, and – what is so important to the beginner – your strong tradition.

To learn the basics of an European not only patience and experience, but also exercise over and over again, By the end of your first steps you may have only touched the surface when you enter this fascinating world of calligraphic strokes.

During my visit at the TypeBank studio in Tokyo I was surprised by how perfectly the optical problems of the Latin alphabet were mastered by their designers. The studio had a warm atmosphere. No haste or hectic pace like you feel in an American design studio. The drawings were executed with immense care. Each letter was in perfect proportion, and the fitting of the characters (which is so important in the Roman alphabet) was carefully considered.

Beside my interest in their drawing of the Roman letters, this day at TypeBank awakened in me a special interest in Kanji. After seeing the numerous examples in the studio, I began an intensive study of the structure of Kanji when I returned home, for I wanted to get more information in order to learn as much as possible.

I have experimented to find a solution to bridge the differences in style and basic structure between kanji and Roman characters, which appear next to each other in bi-lingual publications. My interest as a professional type designer was aroused by the possibilities of a more even appearance in the weight and forms of the individual Kanji characters. This was for experimental purpose only.

In Latin book faces we try to achieve a careful balance of the various strokes and elements within each character, since in composition it is the goal to get an even gray type area so important to Western book typography. Japanese composition looks completely different to us. Our attention is attracted by the light and dark characters in Kanji, depending on how many strokes were used to build up the Kanji forms.

With Takao Hayashi I discussed the crazy idea to widen the dark characters like 聞 and to narrow characters like 人 or 工 (as shown here: 人工). I hoped to balance the different weights of some of the characters through the modifications possible in digital character generation. But in general this was too complicated and did not work, for it interfered too much with the traditional system of Kanji, which is based on a square. A proportional Kanji along these lines would have worked only in the horizontal arrangement of lines, but not in the vertical direction.

Takao Hayashi had unusual patience for all my ideas. Of course he knew the difficulties involved with new Kanji type designs. But I must confess that I learned to understand Kanji much better through all the problems and details involved in the design process. His sudden death was for me not only the end of my studies, but also the loss of a great friend in Japan.

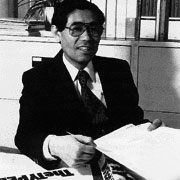

- Takao Hayashi

-

Takao Hayashi’s dedication in digital types started when he became typographer after quitting an Art College. As the original member of Group Typo, he was involved in creation of cold type of Typos with his three friends.

In 1975, Hayashi established TypeBank and his name became well known as he released trend-setting “Now” or “Ajioka Kana” series as a type director.

Hayashi was so distinguished among type designers by his deep understanding and sights for coming era of electronic documentation and ubiquitous computing. He told his ideas about typeface designing and its future in various publications or as lecturer at conferences, thus people regarded him as a guru of digital fonts.

Hayashi died in 1994 when he was 57 years old. The following is the memorial by Hermann Zapf.